The new film art | worlds within worlds

Over the past several years, I’ve started to notice this trend in films that features objects that could surely be called art. They are the journals of Francis Dolarhyde in Red Dragon, the journals and pictures drawn by witnesses in The Mothman Prophecy, the journals and notebooks of children and teen girls in The Ring and the film footage that will kill you that is inside the film in The Ring, and the sheer madness of the wall and window art created by John Nash in A Beautiful Mind. Those just off the top of my head. In each case, the journals, writings, films and other images add another dimension to the film – one that takes us deeper and more inside, revealing to us the soul of the desperate as it journeys its private and dark night.. Each object goes to creating an aura on which the rest of the film will hang. Such journals and films are at the very core of each film – they are the key, the answer, the door waiting to be flung open to reveal that deeper understanding.

What is it about any film that one finds truly terrifying. We may be terrified as viewers, but imagine being a victim and not just a witness. How much more frightening is that? Directors and authors have found a device, a trick, that brings us deeper into any horror film; help us see behind the eyes of both killer and victim. What is it to be in the head of a person when they are about to die? Don’t we all wonder, at some point, what happens then? Using a journal or film as a device, directors and writers offer an opportunity, an advance viewing of how the mind churns dark and confusing thoughts, how we process our fear so different, yet in so many ways, remarkably alike.

Who can forget the fat and fabulous journals of Frances Dolarhyde, bound in thick leather and bearing oversized 9 x 11 velum pages onto which Frances has pasted what seems to be essentially an entire inner world, beginning in early childhood through the present. Inside you find pictures of grandmother D, an abusive woman who raised him and is always threatening to “cut it off” because he’s a “filthy little beast” bed-wetter. Mostly though, because he’s just a little boy and one gets the sense that she didn’t sign up for this. Where his parents are remains a mystery, all we know is that it is she who raised him and it wasn’t good.

Dolarhyde’s journal bears old photographs of his deceased and wicked grandmother, her face scribbled out, cut-up rearranged, her eyes replaced with repeating butterfly wing spots, her teeth emphasized for we know that it is biting that really gets Dolarhyde off. . There are photographs of Frances as a young boy, his face overdrawn, his cleft-palette mouth especially darkened by black pen, and news clippings that detail his own killings in which he is dubbedc “The Tooth Fairy” by the soon to be dead Freddie Lounds at Tattler magazine. More, clippings of our old friend Hannibal Lecter, fellow serial –killer and inspector Will Graham (Ed Norton), laid up in the hospital after Hannibal tried to kill him. And in between all of this is page upon page of text, in it’s rather interesting handwriting – legible and definite This journal is nothing less than a work of art. It is life, bound.

Think of the journal drawn by Mary Klein in Mothman Prophecy before she dies. Using only what she has with her in the hospital after her car accident, Mary (played by Debra Messing), uses the tools she had – her eyeliner and lipstick – to draw the winged figure that she sees and that causes such fear and caused the accident in the first place. The creature of which she says to her husband (Richard Gere), “You didn’t see it, did you.” She draw the figure over and over again. It is a moth-man, with heavily darkened wings or a dark cape, colored in with her dark kohl eyeliner, with eyes red as her blood-orange colored Shisheido, colored over and over again so heavily that it almost looks as though it were drawn with oil paint.

Like Dolarhyde’s fat and huge journal, and Mary Klein’s heavily drawn lipstick-red eyes and the images drawn by the young victims in The Ring, each of these characters reveals some turmoil of their inner world – the dark journey of the soul as it begins a slow descent into madness or a journey of extreme horror and fear.

John Klein (Richard Gere) is initially so blind to Mothman that he may never have found his wife’s hospital journal were it not for the distant figure of the attendant who informs him that before Mary died she had been “drawing angels” as if “she knew,” the attendant says.

Yes, Mary Klein did in fact know, but it had little to do with angels by any standard definition. Yes, Mothman is the harbinger of death, the symbolic manifestation of the soul’s winged flight and journey to the after world. More, it seems that he is often or maybe only seen by those who have some prescience, just like our young friends in The Ring. You have to know you are going to die, or at least, the process must be started, otherwise, you do not see the way John Klein is in the same car with Mary when it crashes, but doesn’t see the winged Mothman.

You are either sensitive or not sensitive, as Annie (Cate Blanchett) would say in The Gift (anyone else noticing these two word titles: the briefer the better. Concept based horror, and simplified.) One cannot draw what one have not seen, and in these films anyway, the very fact of seeing has rendered you in deep doo doo. If you see it – and the it will change from film to film - you will die.

Fear.com had the same premise, though it wasn’t done well enough to succeed and instead, fell flat on it’s face. It could have been a great film. After all, it shared the same conceit as these others noted here - all of which I think are excellent films. Yet Fear.com didn’t get into our heads the same way. Maybe if they had made the Web site weirder or shown us more of the victims inner world we would have believed. As it stands, the site wasn’t intricate enough, it wasn’t, and I hate to say it, artistic enough. Only a work and I’m convinced of this, great art, would be so terrifying. It has be done or drawn, compiled, painted, filmed, directed whatever – by someone who, like the victims in these films, is sensitive.

How very effective are the journals and the actual video (the film inside the film) in The Ring. We see the first victim’s journal with images of her teen idols and her dreams of one day being a being a bride, all pasted so neatly into her binder. Within time, as each day passes bringing her closer to her fate, they are beings transformed with dark veils scratched over their face and the sun blotted out with a heavy black pen that seems to scratch off the face. Or, as the seven days progress, we begin to see images of dying horses washed ashore by the tide, beneath each picture are the words “Why is this in my head?” written in chicken scratch beneath the images. Even Naomi Watt’s prescient son, who for the record is the only one who knows this Samora chick in the well is bad news, maintains a gallery of what he sees. Who among us can forget the maddening sound of his pencil scratching broad and deep circles on the desk as he draws the same dark ring over and over and over and over again and with such a dark fury. It’s so intense, so deep, that you just might fall into the blackness of this dark, spinning well that he is so compelled to draw.

Perhaps we have developed a whole new category of art – that of horror movie films, or perhaps we are moving closer and backward again to films like Chien Andalou, the famous surrealist film that very much touches on the same themes as the clip in The Ring – themes of rot and decay, rebirth, nothing less than life – from it’s first and primal state of maggot or egg, all the way through rot and decay.

John Nash’s office as displayed in A Beautiful Mind (a flawed film in many ways, and one in which I think the real John Nash is somewhat degraded, and note that he did not work with the biographer on the book; this was unauthorized, but that’s a whole other piece). The offices though, go a long way to illustrating the inner-world of the schizophrenic,.the walls used like a bulletin board, completely covered from floor to ceiling with news clippings circled and patterns found in magazines. It’s easy to see how certain things jumped out at him.

When I worked at The Atlantic Monthly we had several people who would send us back our magazine, only they had, like Nash, circled certain words and headlines, phrases, and found what they believed to be code. I suppose you could review any magazine and newspaper and if you circle the right words, you could decipher a whole new meaning than what was intended. Like Robert Redford in Three Days of the Condor, you make it your job to reveal the secrets that you are so sure are hidden in the text. It’s not so crazy: certain books and journals did contain code, and newspapers, personals, even literary fiction has been used by various governments and groups to convey secret messages that are two way blind.

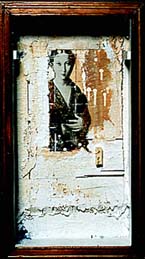

All of the devices noted here, the rooms, the journals, the film footage, remind me of the famous cabinets of Joseph Cornell or Rosamund Purcell, two artists capable of creating a whole atmosphere within a single piece of art. A richly layered and textured realm where we see what they want us to see. Check the credits for these films and you’ll most often find that design firms had been hired, along with special stylists, to create these devices. What a job, I think as one who even now creates cabinets and has worked with Purcell and others on such projects. Imagine the films without these devices; they would be dull and void and not quite as scary. They would lose the spectacular affect of what it is to be completely mad.

Perhaps we should all put up a bulletin board or buy a blank journal; paste whatever we want or write every day – in a way, we do this when we blog. Ask of yourself, how much of your inner-world do you reveal and what are you bringing forward to show us. The whole lot like Frances Dolarhyde or is your world one of butterflies and Easter bunnies.. If you’re mad enough, perhaps your work could be featured next. There’s a Samora in all of us – it just depends on what we do with it that helps determine how affecting it could be. Maybe we have found, after all, a new venue for our psyche. You never know.

sadi ranson-polizzotti

<< Home